The world is heading into a future with many more older people. The impact on human societies could be devastating if we continue to structure our economies on conventional principles of growth, production and consumption. So how can we reframe this issue in ways that avoid contentious topics like eugenics or population control?

There can be no doubt that the demographic shift toward an aging population potentially has substantial implications for our collective consciousness and group decision-making systems. It's a dual-edged sword, for while it brings the potential for increased wisdom and experience it also risks declining innovation and the distortion of societal priorities.

As the proportion of older individuals increases, the economic impacts will be accentuated, particularly if resources are needed to tackle pressing global issues like climate change or geopolitical conflicts. This shift also poses questions about whether current policies around fertility, food production, and gene therapies posing as vaccines, for example, are either appropriate or sufficient in order to address the economic and social challenges of an aging world.

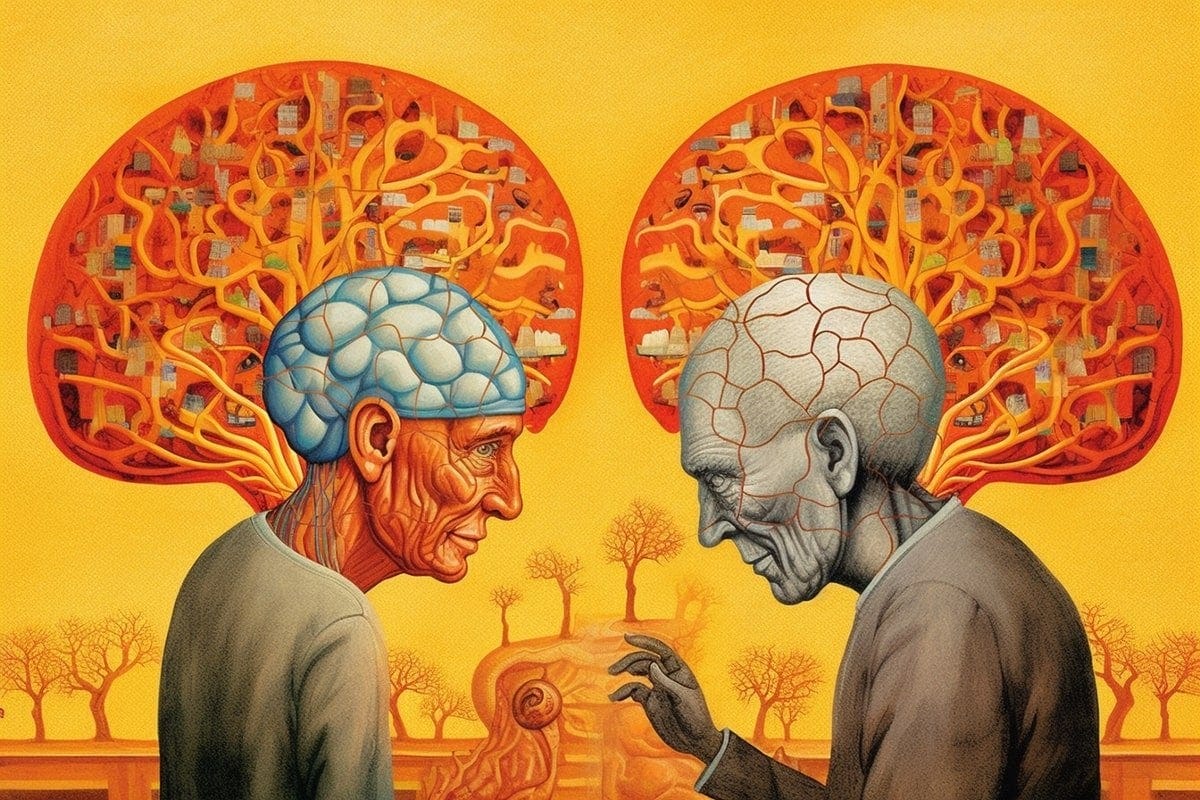

Our civilization's collective mind, or noosphere, catalysed by differing worldviews, relies on the synergy of ancient human instincts and knowledge traditions, long-established institutions, and technology in order to function effectively. This collective mind faces significant changes as:

Individual cognitive abilities (cells in the collective brain) decline with age, impacting the ability to process new information and adapt at local levels.

Institutions often lag behind the evolving needs and perspectives of the aging population, leading to misalignment and a conservative swing in terms of policy.

Technological advancements, particularly in the emerging fields of open source AI and machine intelligence, hold out the promise of enhancing everything from thinking to communications and productivity, but also introduce doubts about their easy integration into existing socio-economic systems.

At least without some of the potential technologies currently in development for increasing longevity and reversing the ageing process, individuals expect to experience some degree of cognitive decline with advancing years, which affects things like reflex speed, memory, analysis, physical orientation, the efficacy of decision-making, and the ability to conjure up new ideas.

The conservative bias that often accompanies ageing populations can often lead to a political landscape that is less responsive to contemporary realities. This streak of conservatism is likely to be exacerbated without better representation of younger generations in systems of governance, leading to potential misalignment with broader societal needs and slowing the ability of society to adapt to new challenges.

As societies age, economic dynamics shift. Older populations may alter market behaviours, such as real estate and investment patterns. Additionally, the incumbent gerontocratic influence in academic and business circles can impede 2nd-order change and ontological reinvention. The tendency for the elderly to prioritize legacy over innovation, coupled with a predisposition to live in the past, may delay critical social advancements, affecting sectors like energy, health, education and governance.

Innovation is critical for healthy societal advancement; much more so than continuous economic growth. The generational divide impacts how innovation is pursued and adopted. Older populations almost always resist new technologies, proposals, and ways of doing things, potentially slowing down progress.

The ageing of the global population represents both a challenge and an opportunity for re-imagining our collective approach to progress, along with its raison-d'etre. The major risk of a senescent collective mind is that the process of decision-making becomes ultra-conservative and even moribund, potentially stalling crucial advancements needed by the society. Such conservatism will manifest in slower policy adaptations, resistance to new technologies, and economic imbalances that favour established interests over emerging necessities.

However, there's also a chance to leverage the collective wisdom and experience of an older population while integrating the innately innovative capabilities of youth. Ensuring that national governance, market dynamics, and technological development accommodate both the experience of the old and the creativity of the young is essential for navigating the complexities of an aging world. Also of interest is the fact that the most youthful countries are located in the global South.

Nearly half of Niger's population, for example, is under the age of 15, making it the country with the highest percentage of young people. The top ten countries in the world with the highest share of young people are all in Africa and that heralds a shift in our civilisational model one would think. By 2050, one in four people will be African. Asia's population will remain substantial, but its growth trajectory is different from Africa's. By 2050, Asia's population is projected to be approximately 5.2 billion. While the growth rate is slower compared to Africa, Asia will still be home to a significant portion of the global population

A cautionary note. Most of my readers are WEIRD. This acronym means Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. It accurately describes a specific subset of societies - I am tempted to give them the collective noun of the 'global north' - that are most often the focus of psychological, social, and medical research. Many studies and most research is conducted with (mostly male) contributors from the WEIRD societies. It's fairly obvious that this does not represent the global population as a whole, even though we often pretend that the outcomes can be applied everywhere. It’s not so obvious that our minds have been colonised by the ideas of these societies.

Such is the case with our ageing society. We must learn to think differently about this topic when around 7.2 billion people on the planet will come from the global south and only around 2 billion from a WEIRD background in just 25 years time. Additionally, most cultures in the global south, using that term metaphorically to include China rather than strictly geographically, represent ancient wisdom traditions stretching back over 4,000 years. WEIRD societies are a recent anomaly in that context.

Addressing the challenges I have mentioned requires an approach that harnesses the strengths of all age groups and belief systems. By engaging a genuinely global mindset, a community of mind symbolizing the human family as a whole, we can mitigate the risks associated with an ageing population in differing parts of the world, ensuring that our 'collective mind' remains vibrant and evolves in ways that are capable of addressing the significant challenges ahead.