As someone on the autism spectrum, I find violence unnatural and intimidating. Crass and ignorant too. It's impossible to reason with asininity. So when faced with anger of any description, I just retreat into silence.

The assertion that violence is native to us humans has been a long-standing conviction. But it’s a myth. Besides, it greatly distorts the complexity of human behaviour and neglects the significant influence of social, cultural, and environmental factors. While historical instances of violence seem to suggest a natural tendency towards aggression, meticulous analysis suggests that violence is not an inherent human trait at all but rather the outcome of certain conditions.

Anthropological studies provide compelling evidence that runs counter to the notion of innate violence in humans. Many pre-modern societies practiced peaceful coexistence, resolving conflicts without resorting to belligerence. The !Kung San people of the Kalahari Desert exemplify a society where cooperation and sharing are paramount. Anthropologist Richard Lee observed that disputes among the !Kung are typically settled through discussion, indicating that violence is not a universal human quality. It is one shaped by cultural norms. Furthermore, the concept of the "noble savage," popularised by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, suggests that early humans lived harmoniously with nature. Evidence from a number of hunter-gatherer societies supports this perspective, revealing that interpersonal violence was less common than previously believed. Research by anthropologist Christopher Boehm demonstrates that egalitarian societies employ mechanisms to avoid violence, such as social sanctions against aggression.

Psychological studies further undermine the argument that violence is an innate human characteristic. Theories like the 'frustration-aggression' hypothesis suggest that aggression arises from external factors rather than inherent inclinations. According to this theory, violence is a normative response to frustration experienced in specific contexts, highlighting the importance of situational variables. And developmental psychology goes further, emphasising the important role of upbringing and environmental influences.

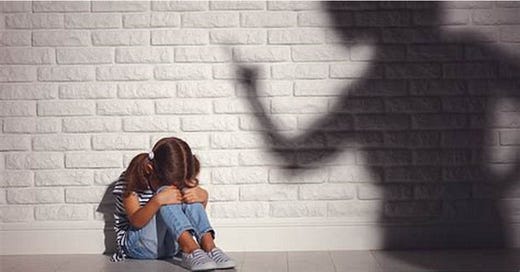

Studies indicate that children exposed to domestic violence are much more likely to exhibit aggressive behaviours later in life. Conversely, children raised in nurturing environments often develop empathy and non-violent conflict resolution skills, reinforcing the idea that violence is a learned trait rather than innate. Historical perspectives also show that the levels of violence in societies fluctuate significantly over time and across cultures, indicating that it's by no means a fixed aspect of human nature.

Steven Pinker, in his book "The Better Angels of Our Nature," presents a compelling argument that human societies have become less violent over the past two centuries. Citing data showing a decline in homicide rates and warfare since the Enlightenment, he suggests that education and societal advances encourage peaceful coexistence. The rise of international laws and norms against all forms of violence, including human rights treaties and conflict resolution frameworks, reflect a collective human effort to curb violence, highlighting the proposition that societies can and do evolve away from aggression.

Sociological perspectives further emphasise the role of community structures and social institutions in shaping human behaviour. The prevalence of violence in some societies can almost always be traced back to impoverished socio-economic conditions, systemic inequalities, and a lack of access to education or resources. Regions plagued by destitution and political instability frequently experience higher rates of violence. Research has shown that improving social conditions—by increasing educational opportunities, reducing poverty, and promoting social justice—can lead to lower rates of violence. The World Health Organisation identifies these determinants as critical factors in preventing violence, further supporting the argument that violence is a response to external conditions rather than an inherent quality.

So we can conclude that violence is not an innate quality of humans, as borne out by the evidence. In any case, such beliefs fail to consider the substantial influence of cultural, psychological, and social factors on human behaviour.

This implies that by interpreting violence as the product of specific circumstances, we can find pathways to promote concord and reduce conflict, primarily through prolonged social changes and education. By recognising violence as the unwanted product of specific states rather than an inherent human trait, we can also explore enlightened ways to address its manifestations, particularly in the contexts of domestic violence, sentencing for violent behaviour, and the socialisation of youth into non-violence.

Statistics indicate that a significant number of women experience violence from intimate partners or people they know. According to the World Health Organization, about 1 in 3 women worldwide have experienced either physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner or sexual violence from a non-partner at some point in their lives.

To effectively combat domestic violence, especially that perpetrated against women, a comprehensive strategy is essential. Instruction and awareness campaigns can play a crucial role in dismantling harmful stereotypes and promoting understanding of healthy relationships. Such initiatives must target both men and women, emphasising the unacceptability of violence and the importance of consent. Alongside this, providing accessible support services for victims—such as shelters, counselling, and legal assistance—is vital. These services need to be well-funded and widely advertised to ensure that victims can seek help without fear of stigma.

Community engagement is another key component in addressing domestic violence. Involving community leaders and organisations can sharpen a culture of accountability and support. Training programs can equip community members to intervene safely in situations of potential brutality and provide assistance to the injured party. Additionally, policy and legal reform is needed to strengthen protections for victims. Law enforcement agencies must be trained to handle domestic violence cases effectively, ensuring that while stricter penalties should apply to perpetrators, the focus should be on rehabilitation and reform.

When considering jail sentences for violent crimes, it's important that the justice system is able to weigh accountability with opportunities for rehabilitation and reintegration into the community. Implementing restorative justice practices can allow both victims and offenders to engage in dialogue, fostering better mutual understanding and healing. This approach is particularly effective for minor offences, encouraging accountability without perpetuating cycles of violence. For minor misdemeanors, diversion programs that help redirect individuals to community service or educational initiatives can help reduce recidivism. These programs can also address the underlying issues contributing to violent behaviour, including upbringing, poor parenting, substance abuse, or a lack of schooling.

For those sentenced for violent crimes, tailored rehabilitation programs should focus on addressing the root cause of their delinquency. This might include cognitive-behavioural therapy, anger management classes, and vocational training, all aimed at helping individuals reintegrate into society as productive citizens.

Obviously, prevention is better than cure. To cultivate a culture of non-violence among today's youth, a number of strategies can be employed. Bringing conflict resolution and communication skills into school curricula can equip young people with the tools they need to handle disputes non-violently. Programs that teach empathy and respect for diversity are particularly useful in this regard—and acutely lacking these days. Establishing mentorship initiatives that connect youth with positive role models can also have a huge impact, providing guidance that nurtures resilience and non-violent resolution of potential conflicts.

In times past, military service in the form of conscription claimed to produce young people with discipline and fortitude. Today, encouraging youth participation in community service and local initiatives has been found to instill a sense of belonging and responsibility that is hard to achieve any other way. Engaging in constructive activities helps build social bonds, reducing the likelihood of violent behaviour. Additionally, promoting parenting programs that teach non-violent communication and conflict resolution skills can create positive home environments, as parents equipped with these abilities are far better able to model non-violent behaviour for their children.

Understanding violence as both a product and a reflection of our society means that we should be able to shape conditions that are more conducive to conviviality, in addition to designing more informed methods of eradicating violence and outrage in its various forms.

By inculcating a culture of composure and non-violence in schools, support services, and the community, we might gradually be in a position to outlaw excessive outrage and its resulting behaviours. We need to rethink how to address domestic violence, reform sentencing practices to focus on rehabilitation, and find more effective ways of instilling non-violent values in our youth. We should desire a culture of peace and tranquillity. If we can create such a culture, it will significantly reduce violence in society across the board.