Surveying the present era, it's almost impossible to escape the sense that stupidity is endemic—woven into the fabric of our institutions, our technologies, and even our collective imagination.

Rarely is it a matter of mere ignorance. Instead, we see intelligent people and sophisticated organisations making decisions that appear, in retrospect, not just misguided but profoundly foolish—decisions whose consequences ripple far beyond the original context, shaping the future in ways that are increasingly unpredictable, and often hazardous.

Stupidity in this sense is not confined to politics or the spectacular failures that attract headlines. It's distributed across all domains: business, education, law, international agencies, and especially in the world of entrepreneurial activities. Here, a web of poor decisions, misaligned incentives, and cognitive blind spots conspire to produce outcomes that are not only sub-optimal, but sometimes existentially threatening.

Corporate Myopia and the Illusion of Profit

The corporate world provides a field study in how intelligence can be subverted by systemic pressures. For decades, business chiefs have championed deregulation and lower taxes as levers for growth, believing these measures essential for profitability and shareholder value. Yet, in their quest for short-term gains, they routinely undermine the very foundations that enable an enterprise to remain viable.

This myopia is not born of stupidity in the conventional sense; rather, it's the product of an incentive architecture that penalises long-term thinking. Executives are lauded for quarterly results, not for stewarding the company’s future over decades. The result is a corporate ethos where cost-cutting, regulatory arbitrage, and labour exploitation are valued, while investments in resilience and social capital are viewed as costly distractions.

Ironically, these strategies have destabilised the social and legal frameworks upon which business depends. The drive to weaken regulations and labour protections has created fertile ground for authoritarian governance and economic unpredictability. As a consequence, many organisations now find themselves operating in hostile environments, their freedom to manoeuvre sharply curtailed by the very forces they helped unleash.

Institutional Failure: Bureaucracy and Global Health

International institutions, charged with managing transnational risk, have not fared much better. The World Health Organization’s faltering response to COVID-19 revealed how bureaucratic inertia and political interference can paralyse even the best-resourced and well-intentioned of organisations. The resources and expertise existed. What was lacking was the agility to act decisively and the courage to speak inconvenient truths when they mattered most.

In practice, institutional stupidity manifests as a kind of collective paralysis. When the moment demands adaptation and foresight, organisations retreat into process, hierarchy, and protocol. The result is delayed action, confused messaging, and—ultimately—a loss of public trust. This erosion is not easily reversed: once confidence in an institution’s competence is lost, its capacity to coordinate collective action, especially in a crisis, is permanently impaired.

Entrepreneurial Recklessness: Innovation Unmoored

Entrepreneurship, so often framed as the engine of progress in an age of the 'wunderkinder' is likewise susceptible to its own forms of folly. The culture of the start-up, and the fanatical quest for 'unicorns' - particularly in technology - values disruption and scale above all else. In the race to capture markets and attract venture capital, ethical considerations are often marginalised. The cryptocurrency boom is a case in point: alongside genuine innovation, the sector has spawned a proliferation of scams and fraudulent schemes, with little regard for their impact on investors or the broader economy.

This recklessness is not without consequence. Beyond the immediate harm to victims, it fosters a generalized scepticism toward innovation—a corrosion of the social trust that genuine breakthroughs require. The volatility and periodic collapse of crypto markets offer a blatant illustration of what happens when regulatory oversight and ethical responsibility lag behind technological possibility.

When Short-Termism Infects Society

If stupidity were limited to individual companies or agencies, its effects might be contained. But the reality is more insidious. When business enterprises and elected officials prioritise immediate self-interest without considering the wider implications, they set off a cascade of unintended consequences: the attrition of trust in even our most venerable institutions, the amplification of inequality, and the destabilisation of entire economies.

The political landscape, marked today by rising authoritarianism and populism, is both a symptom and a cause of this pathology. Failures by business and political elites to defend the common good have created spaces where misinformation flourishes and public faith in democracy is withering. The system becomes self-reinforcing: shortsighted decisions breed cynicism, which in turn makes wise governance ever more difficult.

The Cognitive Roots of Stupidity

What we witness in institutional inertia, corporate myopia, and entrepreneurial recklessness is best understood as the surface manifestation of a deeper cognitive and social disorder. The paradox of human intelligence is that we possess remarkable capacities for abstraction, creativity, and cooperation, yet repeatedly fall prey to biases and errors that undermine our collective well-being.

This paradox makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. Our brains evolved not for dealing with complexity or a need for farsightedness, but for social navigation and survival in our immediate surroundings. The neural architecture that privileges simple pattern recognition, threat detection, and status-seeking is ill-suited to the demands of an interconnected, rapidly changing world.

Cognitive biases—overconfidence, motivated reasoning, the illusion of explanatory depth—are not quirks, but built-in features. The Dunning-Kruger effect, though sometimes overstated, points to a real and persistent misalignment between competence and self-assessment. In practice, this means that those least equipped to judge a situation often have the greatest confidence in their ability to do so.

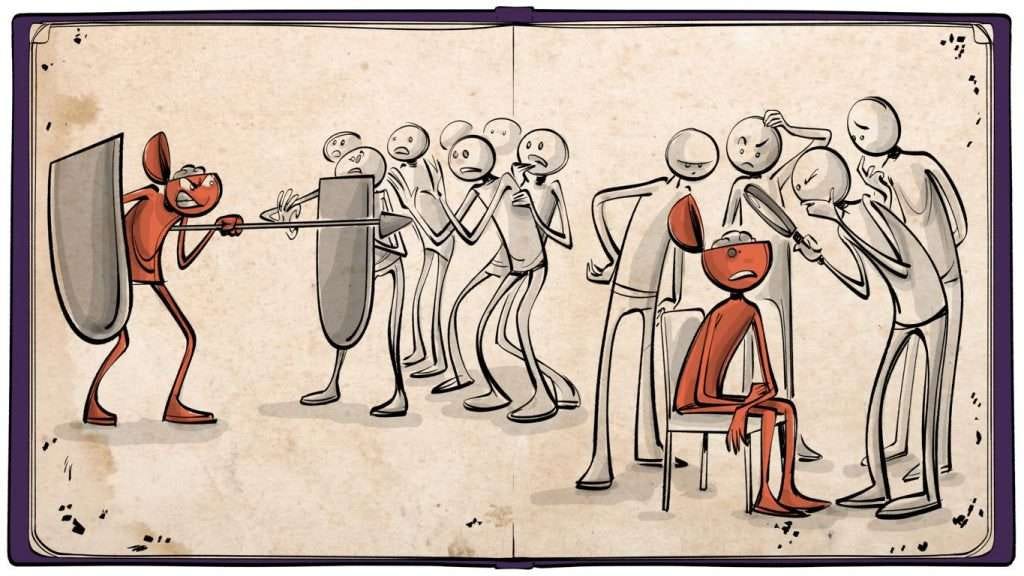

Stupidity as Social Contagion

But stupidity is not merely an individual failing. It is socially transmissible—a contagion that spreads through networks and organisations, often accelerating in the process. As Carlo Cipolla observed, we consistently underestimate both the prevalence of stupidity and the damage it can inflict.

The structural design of digital platforms has dramatically amplified this transmission. Algorithms tuned for engagement reward emotional intensity and polarisation. Accuracy is an afterthought. Network science has shown that falsehoods propagate online far more rapidly than verified information. In this context, stupidity is not simply tolerated—it's optimised for virality.

Even more insidious is our neurological predisposition for conformity. Solomon Asch’s classic experiments revealed how individuals will deny the evidence of their senses to align with group opinion. Robert Cialdini’s concept of social proof explains why entire organisations, or even societies, can cascade into collective folly: we look to others for cues on how to behave, and when the group is wrong, error becomes self-reinforcing.

Institutional Incentives: Manufacturing Myopia

Rather than mitigating stupidity, many institutions inadvertently amplify it. The 'Peter Principle' describes how organisations systematically promote people to their level of incompetence, filling critical roles with those least able to fulfill them. Political systems, for their part, reward emotional resonance and performative simplicity over substantive expertise. Politicians who appear “relatable” in their ignorance often fare better than those who grapple openly with complexity.

Corporate incentives are even more structurally perverse. Executive compensation is almost universally tied to short-term performance metrics—quarterly earnings, stock price appreciation, annual targets. Board members and institutional investors, themselves under pressure for rapid returns, reinforce this bias. Functional MRI studies confirm that short-term rewards activate deep neural circuits, overpowering the more deliberative pathways required for long-term planning.

The effect is what organisational psychologists term “temporal myopia”: an institutional blindness to future threats and opportunities. In this environment, executives who champion sustainability or resilience are not simply ignored, but actively sidelined. The system itself becomes a machine for producing systematically foolish outcomes, regardless of the intelligence or intentions of the individuals within it.

Metacognitive Blindness and Motivated Reasoning

Perhaps most troubling is our inability to recognise these failures as they occur. The Socratic insight—that wisdom begins in the recognition of our own ignorance—has little traction in public life. Instead, we succumb to motivated reasoning, using our cognitive resources to defend identity and ideology rather than to seek the truth.

Neuroscience provides a stark explanation: when confronted with evidence that challenges our beliefs, the brain’s emotional centre's activate before the rational faculties can engage. This is not a matter of education or intelligence. In fact, educated individuals are often more adept at rationalising their biases, using their skills not to uncover error, but to justify it.

Emergence: The Systemic Logic of Collective Stupidity

The cumulative effect of these individual and institutional failures is what systems theorists call emergence: outcomes that cannot be predicted or explained by examining the parts in isolation. Financial crises provide a vivid illustration. Each trader or executive, acting within a framework of individually rational incentives, contributes to a dynamic that ultimately produces collective disaster. The “wisdom of crowds” inverts, becoming what Charles Mackay dubbed “extraordinary popular delusions and the madness of crowds.”

Climate change denial is another emergent phenomenon. The interplay of individual dissonance, institutional inertia, and polarised identity politics creates a network of reinforcing feedbacks that render the system resistant to any form of corrective action. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed a similar dynamic: psychological biases, institutional fragmentation, and political polarisation combining to produce outcomes no single actor intended or could control.

Toward Systemic Remedies

If stupidity is emergent and systemic, its remedy must also be systemic. The problem cannot be solved by merely identifying and removing “stupid” individuals, because the stupidity resides in the relationships, incentives, and feedback loops that shape behaviour at every level.

Traditional economic models, which assume rational actors, ignore the hidden costs of stupidity. Behavioural economists estimate that cognitive biases and misaligned institutional incentives may reduce global GDP by as much as 15-20 percent annually—an impact far greater than most visible crises.

Is stupidity unavoidable? Given the architecture of our brains and the ways our societies are structured, it might seem so. However, recognising how stupidity operates allows us to reduce its impact. Organisations that formalise their decision-making, encourage diverse perspectives, and actively guard against cognitive biases consistently achieve better results. By redesigning systems to reward long-term benefits instead of short-term gains, we can shift the collective focus toward enduring well-being. And when problems do arise, precisely targeted interventions—much like systemic acupuncture—can help restore balance and resilience.

Most promising, perhaps, is the cultivation of genuine intellectual humility—not as a rhetorical flourish, but as a core operating principle. As Bertrand Russell noted, “The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent full of doubt.” If stupidity sticks, then recognising the adhesive properties of our collective folly may be the essential first step toward freeing ourselves from its grip.