The Phase Transition

From Literacy's Emergence to Digital Eclipse

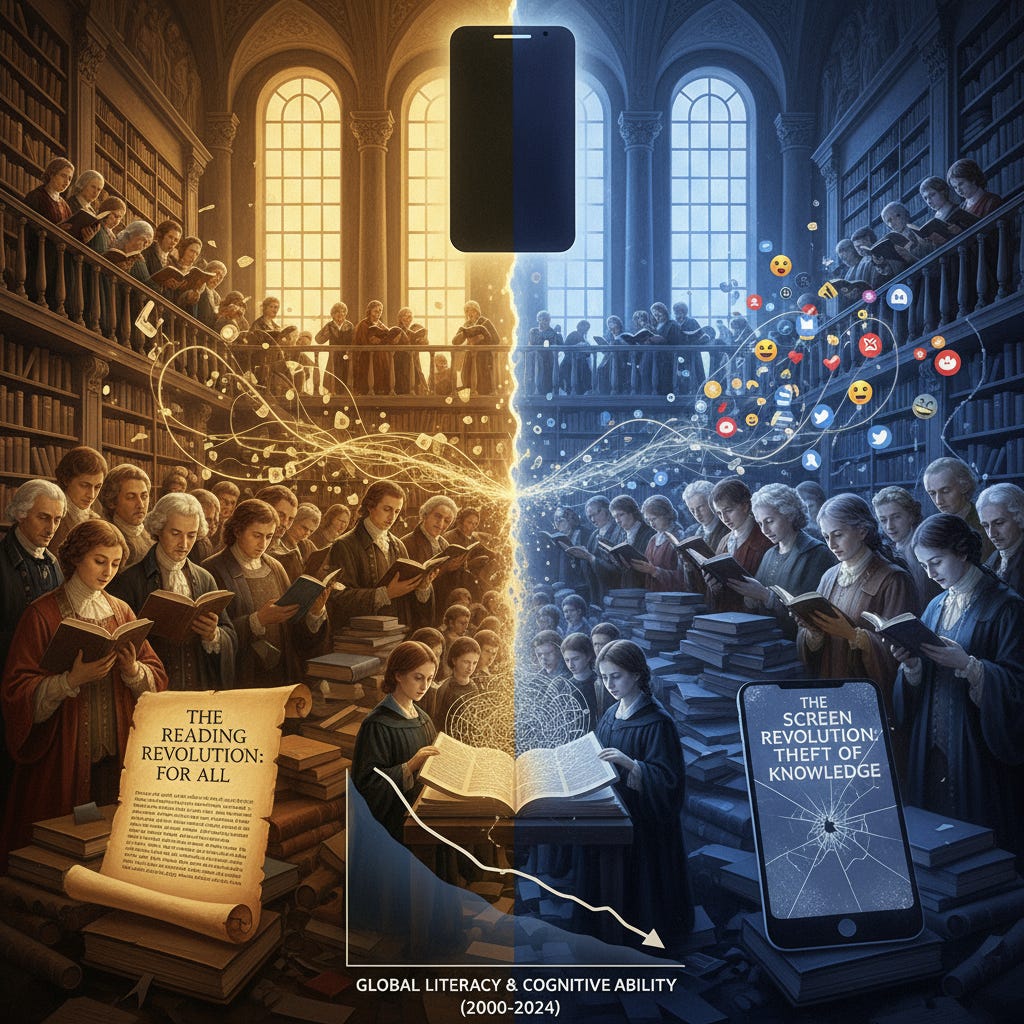

In the evolving architecture of our collective consciousness, few transitions have so profoundly reconfigured society as the reading revolution that dawned over three centuries ago. This quiet upheaval – the mass diffusion of print and literacy – unlocked a vault of knowledge once sealed to all but the elite. Books became the neural pathways of cultural transmission, synaptic bridges linking minds across continents and generations. In their pages, ideas could sediment and accumulate, allowing each generation to build on the last in a recursive spiral of civilisational advance. The Enlightenment, democracy, socialism, scientific revolutions – all sprang from this newfound connectivity of thought. Yet now, in our own time, those hard-won pathways are deteriorating. The cognitive scaffolding erected by print culture shows cracks, and the flow of knowledge through society is choked by entropy. What was once a robust network of enlightened minds is in danger of devolving into a fragmented void.

Evidence of this reversal is all around us. In an age of unprecedented information, reading itself is in relentless decline. By many measures, we’re drifting from print’s shorelines into uncharted waters of post-literacy. In the United States, the share of adults reading for pleasure has plummeted by roughly forty percent in the past two decades. Over a third of UK adults now confess they rarely, if ever, read books. Children’s literacy is at its lowest ebb since records began – a “shocking and dispiriting” collapse, to quote a National Literacy Trust report.

The publishing industry, once the powerhouse of our knowledge commons, is in crisis: titles that a generation ago might have sold in their hundreds of thousands now struggle to reach a few thousand readers. Most alarmingly, a 2024 OECD survey finds literacy levels stagnating or falling across much of the developed world. These aren’t the transient dips one might expect from a war or economic depression; they mark a systemic shift. Our collective capacity to engage with long-form text – to sit with complexity and refinement – is eroding. It’s as if a great library is slowly burning in front of our eyes, not in one cataclysmic bonfire, but through the quiet neglect of millions who have turned away from the printed page.

What force could be precipitating this great unwinding of the literate era? A famine? A political purge of books, perhaps? No. Something far more insidious and intimate: the smartphone. The mid-2010s saw the smartphone’s mass adoption – an inflection point in our evolutionary trajectory as significant as any technological leap before.

Never before has a tool so rapidly and pervasively transformed daily life. Earlier entertainment technologies, like radio or television, occupied discrete pockets of our attention. The smartphone, by contrast, demands our whole being constantly. It’s a strange attractor for the mind, pulling our gaze and thoughts into its glowing embrace at every opportunity. Through carefully calibrated doses of dopamine – the ping of a notification, the endless scroll of personalised feeds – it has woven itself into every idle moment, every gap in our day. The average person now spends around seven hours staring at screens each day; for the emerging Gen Z, that figure creeps towards nine.

A recent analysis in The Times even suggested that today’s students will inevitably spend roughly twenty-five years of their lives on digital devices, eyes locked to flickering pixels. This is nothing less than a phase transition in the ecology of the mind. Where once people filled quiet moments with introspection, conversation, or the companionship of a book, now a luminous rectangle mediates nearly all experience. One might recall that the printing press was a watershed that set humanity on a new course – spreading knowledge like wildfire. The smartphone, by comparison, is proving to be a watershed of the opposite kind: a flood that, while connecting us in some ways, is drowning out the slower, deeper currents of introspection and knowledge.

If the print revolution represented an extraordinary infusion of knowledge into society, the screen revolution can be seen as a vast siphoning away of that knowledge. All the hours collectively spent with books – absorbing War and Peace or Origin of Species, parsing arguments, pondering, revisiting passages and letting insights ripen – are now diverted into the always-on drip of digital trivia. Our forebears saw the rise of literacy as enlightenment; today we witness an ominous eclipse of that state.

The metabolic flow of knowledge through time, once accelerated by print, is slowing as attention splinters and decays. Never have we had access to more information, yet rarely have we grasped less of it in meaningful ways. The smartphone’s constant feed offers novelty and incentive, but it’s an impoverished diet for the human mind – all sugar and no sustenance. We gorge on memes and short videos while skipping the intellectual meals that truly nourish. What is stolen is not merely time for reading, but the capacity to read – to engage profoundly, without distraction or impatience. The result is a kind of cultural malnourishment, a stealth theft of wisdom from the average person. In place of the broad daylight of cognition, we have the neon buzz of endless entertainment. And as this condition becomes the norm, it has been quietly hollowing out some of the most vital pillars of modern civilisation.

Our universities find themselves on the frontline of this crisis. These institutions – medieval in origin, yet for centuries at the cutting edge of knowledge – are now enrolling the first cohorts of truly “post-literate” youth. Today’s students have grown up not in libraries or under the tutelage of expansive novels, but in the glow of short-form videos, video game gratification loops, and algorithmically curated feeds, punctuated increasingly by AI-generated conveniences. They arrive on campus tethered to devices and, often, unmoored from long-form reading habits.

Professors have begun to notice the seismic shift. Many bright young people, products of one of the most literate educational systems in history, now find classic literature almost impenetrable. A recent study of English majors in the US found that a majority struggled to comprehend even the opening paragraph of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House, a serialized story that Victorian children eagerly consumed in their day. In interviews and essays, students openly admit that a reading load which twenty years ago would have been typical – say, a Jane Austen novel one week and Dostoevsky the next – now feels forbiddingly dense and time-consuming.

It’s not simply a matter of workload; it’s the manner of thinking that proves difficult. Students find it challenging to hold complex plots and subtle details in mind, to read between the lines or appreciate subtle irony. “It’s like asking them to run a marathon when they haven’t learned to walk,” one literature professor lamented. Another educator wryly observed that many undergraduates today are, in practical terms, functionally illiterate when it comes to absorbing complex texts. This is not meant in the literal sense – they can read words on a page – but in the deeper sense of literacy: the ability to engage, analyse, and reflect.

The most ancient function of the university – the transmission of knowledge from one generation to the next – is faltering as a result. Writers like Shakespeare, Milton, and Jane Austen, whose works travelled like messages in a bottle from one era to another, now wash ashore unopened in the hands of a generation adrift amid digital flotsam. The synaptic bridge that once linked each new wave of students with the cumulative wisdom of ages past is crumbling. It is a breakdown of continuity that feels eerily reminiscent of earlier dark ages: one is drawn to recall how, with the fall of the Western Roman Empire, libraries decayed, books gathered dust unread, and a treasure of classical literature vanished from common memory for centuries. That ancient thread of learning, which was painstakingly re-tied in the Renaissance, appears to be fraying once again.

The implications of this reading collapse extend way beyond literary appreciation; they point to a broader intellectual tragedy. Immersive reading is not a virtuoso hobby for the few – it has been, historically, a foundation for the many intellectual skills modern life requires. Studies in cognitive science have long associated regular reading with improved memory, stronger attention spans, richer vocabularies, and enhanced capacity for analytical thinking. People who read often were shown to have better focus and even a buffer against cognitive decline in later life. To lose reading en masse, therefore, is to witness a slow dissolution of some key mental faculties in the population. The data bear this out.

Around the time smartphones became ubiquitous in the mid-2010s, educators and psychologists began to observe a concerning trend. The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which for decades charted steady gains or plateaus in global educational outcomes, suddenly registered declines across numerous countries. Student surveys told a parallel story: compared to their predecessors, teens in the late 2010s reported greater difficulty concentrating, learning new information, or even engaging in deep thought – an unprecedented admission of mental fatigue in youth.

In the US, a long-running study called Monitoring the Future found an inflection point around 2012–2015 where 18-year-olds’ self-reported ability to focus or stay interested in a task nose-dived. Notably, these declines aren’t confined to the young. Across various age groups, studies have begun to register slight drops in critical thinking and problem-solving abilities, suggesting that the malaise seeps through the culture at large. Even the IQ gains of the twentieth century – the famous Flynn effect that saw each generation scoring higher than the last – appear to have stagnated or reversed in several developed nations. It’s as though the collective mind has slipped into a mild cognitive depression. And why wouldn’t it? The mental habits cultivated by constant swiping and scrolling are inimical to the skills required for complex problem-solving or sustained reasoning. When every spare moment becomes an occasion to refresh a feed or watch another 30-second clip, the brain’s muscle for patience and concentration atrophies. We are finding out, in real time, what happens when a society begins to lose the same habits of mind that once propelled it. The result is not only a loss of knowledge, but a tragic impoverishment of the human experience.

For countless generations, educated people have regarded literature and scholarship as among the highest pursuits and deepest consolations of human life. The classics were not worshipped out of dusty reverence; they endured because each era found something vital and true in them – “the best that has been thought and said,” in Matthew Arnold’s resonant phrase. Great novels and epic poems enlarge our capacity for empathy, placing us in other lives, other centuries. Rigorous non-fiction – whether science or history, philosophy or travelogue – extends our understanding of the astonishing world we inhabit and how we came to be. To read deeply is to commune with minds long gone or far away; it’s a kind of quantum entanglement of minds across time, collapsing distances through the transmission of meaning. Such experiences do more than inform us; they nurture our inner lives, giving shape and texture to our sense of self and our understanding of others.

Now consider how smartphones are robbing us of these experiences. Instead of wandering through the gardens of Middlemarch or the forests of Walden, a teenager might spend hours toggling between vapid “story” videos and curated social media feeds that induce envy, insecurity, or outrage. It should be no surprise that rates of anxiety, depression, and loneliness have spiked among young people during the very years their engagement with reading plummeted.

The devices that connect us incessantly also isolate us in subtler ways – creating a culture of constant comparison, FOMO (fear of missing out), and the performative pressure to craft one’s life as content. Meanwhile, the rich, slow nourishment that reading provides – the very thing that could anchor a frantic mind – is absent. The result is a generation that’s at once overstimulated and undernourished, bombarded with information yet bereft of meaning. It is as if we have engineered a culture that answers every surface desire while starving the deeper longings for narrative, for context, for reflection and aesthetic joy. The psychic toll of this imbalance is only beginning to be understood, but one senses it in the pervasive purposelessness and cynicism that cloud so many young lives.

As grievous as these cultural and cognitive losses are, perhaps the most perilous consequence of our post-literate trajectory lies in what it means for thought itself – particularly the kind of complex, structured thinking that modern civilisation rests upon. There is a reason every advanced society placed literacy at its core: writing is a technology for thought, an extension of the mind that allows us to debug our ideas and hone them to a finer edge. The late scholar Walter Ong famously argued that certain forms of abstract, logical reasoning are all but impossible without writing. In purely oral cultures, thought is tethered to the immediacy of speech and memory; it tends to be concrete, situational, and steeped in the rhythms of storytelling or myth. That has its beauties, but try to imagine developing, say, a philosophical treatise or a complex legal code without writing it down. How could one hold all the premises and permutations in mind, or ensure that a long argument doesn’t contradict itself halfway through?

Even a genius like Immanuel Kant needed quills and reams of paper to produce The Critique of Pure Reason, painstakingly refining his dense, 900-page argument over years. Only by “freezing” his thought into written words could he examine and perfect it – and only by reading and re-reading can a student hope to grasp it. Literacy, then, acts as a cooling system for the intellect, allowing us to step back, scrutinise, and build ideas of great complexity. The entire scientific enterprise, from Newton’s laws to today’s multi-author research papers, relies on this ability to record information and reason through writing.

Our political institutions, too, presume a literate citizenry capable of reading bills, following lengthy arguments, and engaging with facts rather than impressions. This is why the slow shift away from reading heralds a cascading failure in our epistemological infrastructure. As the written word loses its pride of place, public discourse has begun to slide back toward the emotive and ephemeral character of oral culture. The world of the screen is indeed a much choppier place than the world of print – louder, quicker to anger, less tempered by reflection. On Twitter and TikTok, the force of a message comes not from carefully marshalled evidence but from immediacy and visceral appeal.

A book cannot yell or weep to sway its reader, but a video or livestream can – bypassing our critical faculties and appealing straight to our emotions. Thus we see the resurgence of modes of persuasion that would have been familiar to pre-literate tribes: argument by charisma, by incantation, by fearmongering and flattery, rather than by substance.

It is no coincidence that conspiracy theories and mystical pseudo-science have found fertile ground online. Laid out on paper, many of the claims peddled by today’s demagogues – whether a denial of basic science or wild allegations of mass collusions – would appear laughably thin. But on a screen, delivered by a telegenic personality with emotive music and sensational visuals, they strike many as compelling. Candace Owens railing against vaccines or a self-styled guru dismissing climate change do not provide robust evidence; they provide an experience, an emotional high that simulates understanding.

In a print-based public sphere, such figures would remain on the fringe, exposed quickly by fact-checking and reasoned rebuttal. But in the algorithm-driven infotainment hall of mirrors we now inhabit, they command vast followings, their ideas ricocheting and amplifying without ever passing through the filter of print-based scrutiny. The rise of this emotive, tribalised discourse poses a profound challenge to the maintenance of a rational, open society. We may soon face the sobering question of whether it is possible to sustain the most advanced civilisation in history on the fragile cognitive apparatus of a largely pre-literate culture.

Consider what’s at risk: the age of print coincided with an explosion of human creativity, innovation, and progress unlike anything before. It’s not a coincidence. Reading and the habits of mind it engenders have been an invisible force in the background of modernity. Look at the pantheon of scientists, artists, statesmen, and entrepreneurs who shaped the last few centuries – nearly all were voracious readers. Statesmen such as Theodore Roosevelt or Winston Churchill, even amid their hectic lives, devoured books to inform their decisions and broaden their perspective. Churchill famously immersed himself in history and philosophy as a young man, writing ambitious works of history himself; Roosevelt was said to read a book a day, even during his presidency. In the arts, consider a figure like David Bowie, who despite being a rock icon was essentially a bibliophile in glam clothing – he described himself as a “relentless reader” who travelled with a trunk full of books, drawing inspiration from modernist poets and postmodern novelists alike.

The same pattern holds in science and innovation: from Thomas Edison’s personal library to the formative readings that influenced a young Charles Darwin or Albert Einstein, to the quips of a contemporary innovator like Elon Musk claiming he was “raised by books” – the common thread is the influence of sustained reading on creative achievement. Books, by preserving “the best that has been thought and said,” allowed great minds not only to inherit knowledge but to critique and surpass it.

The invention of printing in the 15th century made texts far more accessible, and historians like Elizabeth Eisenstein argue this was the catalyst for the Renaissance and the scientific revolution. Suddenly, a talented student didn’t have to depend solely on a local master’s teachings; she could read widely, even challenge prevailing wisdom armed with new data from a pamphlet or a treatise from across the continent. Innovation thrives in such an environment of open, layered knowledge – a point Eisenstein illustrates with how Renaissance students in print-rich universities were soon outpacing their own professors, fuelling leaps in mathematics and astronomy that left the ancients behind.

Fast forward to today, and we see the opposite dynamic creeping in. A generation that reads less is ironically more dependent on what teachers or the Internet spoon-feed them. If you don’t read deeply, you rarely stray beyond the horizons set by your immediate social media bubble or your formal curriculum. The screen culture, while kaleidoscopic in content, often feeds us more of what we already know (or think we know), reinforcing the familiar rather than challenging it. It also demands minimal effort for consumption, which in turn breeds passivity.

We scroll and click; we don’t wrestle with difficult concepts or invest effort in understanding the unfamiliar. The result is a cultural landscape that, for all its flash and volume, feels curiously stagnant. Pop songs across genres grow more repetitive and formulaic, engineered to hook attention in the first seconds before a listener might skip to the next track. Blockbuster films churn out endless iterations of the same superhero or nostalgic franchise stories – safe bet sequels rather than daring new narratives. In science and technology, despite dazzling breakthroughs in areas like AI, some researchers note that truly fundamental innovations (those “disruptive” leaps that redefine fields) are appearing less frequently relative to the vast amount of research being done. It’s as if we have more people than ever working on problems, with more advanced tools, yet yielding diminishing returns in terms of paradigm shifts.

While multiple factors could explain these trends, one can’t help but see a connection with the diminished role of deep reading and contemplation. A mind raised on quick, shallow bursts of content may simply find it harder to sustain the kind of long, wandering reflection that often precedes creative breakthroughs.

Even literature reflects this simplification: popular novels today, by and large, use fewer unique words and simpler sentences compared to the canonical works of the 19th or 20th centuries. When readers (and publishers) lack patience for complexity, writers oblige by dialing it down. Thus the entire ecosystem of creativity bends toward a lower common denominator – not out of malice or intentional dumbing-down, but as a natural adaptation to an audience with a fractured attention span. If the literate world was characterised by an ever-expanding frontier of ideas and forms – each generation branching out beyond the last – the post-literate world seems bent on circling back, endlessly recycling the familiar motifs of a bygone era. Little wonder that “nostalgia” has become the cultural flavour of the 2020s, manifesting in reboots and vintage aesthetics, as if the collective imagination, unable to forge ahead, is content to rummage in the attic of the past.

Of all the consequences of losing our reading culture, perhaps the most alarming is what it portends for democracy and liberty. Historically, mass literacy has been a prerequisite for self-governance. The spread of reading in the 18th and 19th centuries did more than boost intelligence or empathy; it systematically upended established power structures. At the time, some elites were quite cognisant of the danger: fearful clergymen and conservative critics in the 1700s warned that too much reading – especially of fiction and political pamphlets – could excite the masses and lead them astray.

In a way, they were right. As ordinary people learned to read, they also learned to question, to compare, to think for themselves rather than accepting traditional dogmas. Society became a forum of debate rather than a one-way edict from throne and pulpit. The ancien régime of aristocratic Europe, with its divine-right monarchs and rigid social hierarchy, depended as much on popular ignorance as on brute force. In pre-literate times, authority was reinforced by spectacle and mystique: the king’s ornate portraits and grand processions, the imposing architecture of palaces and churches, the ceremonies that overawed the senses – a whole “representational” culture designed to instil in the populace a reverence and fear that short-circuited dissent. But literate citizens proved harder to awe and more apt to ask uncomfortable questions. As historian Orlando Figes observed, revolutions tended to erupt once literacy crossed roughly fifty percent of a given society – precisely the threshold where reading was no longer a privilege of the elite but a common skill.

In France, on the eve of the 1789 Revolution, an explosion of pamphlets, newsletters, and books exposed the public to the excesses and injustices of the court of Louis XVI. Writers like Voltaire and Rousseau, reaching a broad audience, systematically dismantled the old tenets of absolute monarchy and hereditary privilege. The critical tone of print eroded the old “mystical” legitimacy of rulers, replacing it with Enlightenment ideals of equality and rights. A similar pattern played out in Britain and America earlier, and in Russia later – literacy ignited a fuse in each case. To be sure, literacy alone was not a magic wand (poverty and oppression still triggered revolts in largely illiterate societies as well), but without the infrastructure of print culture to sustain and spread new political ideas, one wonders if concepts like democracy or human rights could have taken root so swiftly.

Neil Postman, writing in the 1980s, argued that American-style democracy was essentially an outgrowth of the print age – an environment where public discourse happened through newspapers, journals, debates and letters that demanded sustained attention and reasoned engagement. In that world, a politician had to be coherent in argument and fact-based, for a reading public could dissect claims at its leisure. The famed Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858, for instance, featured intricate arguments about slavery and economics that each ran for hours – and they were published verbatim in newspapers for citizens to parse.

Jump to the present: such a scene is almost unimaginable. Political speech has largely devolved into sound bites, tweets, and the optics of viral moments. The communication medium has shifted from lengthy printed text to short video clips optimized for sharing. In this new arena, emotional impact trumps evidence, and simplified narratives beat nuanced truth.

It’s little surprise that around the world, populist movements – often led by figures with a talent for showmanship and a disdain for detail – have surged. Research has even indicated a correlation between heavy social media use (especially platforms like YouTube or TikTok) and susceptibility to populist or extremist messaging. Short-form video, in particular, is rocket fuel for demagogues: it bypasses the part of the brain that might otherwise pause to verify a fact or weigh a counterargument, and instead hits the viewer with a concentrated dose of emotional stimuli.

Fear. Pride. Humiliation. Outrage. These are the currencies of the screen-age politician. They offer not plans or proofs but feelings of belonging to a cause, or righteous indignation at some enemy. Such tactics are powerful, but they are fundamentally at odds with the deliberative, informed consent that real democracy requires. A citizenry that cannot or does not read in depth is, in effect, disqualifying itself from the very mechanisms of accountability that keep tyranny at bay. The ancient habit of consulting facts and weighing evidence is replaced by a more primordial habit: following the loudest voice that resonates with one’s immediate sentiments. This is the fertile soil in which autocracy can take root – often with the populace’s enthusiastic support, at least initially, because the autocrat knows how to play the media strings to stir their hearts.

Complicating matters further is the role of the vast technology corporations that dominate this digital landscape. Their business models are predicated on capturing attention and selling it – which, in blunt terms, means they profit most when we’re glued to our screens, feeling emotions that keep us clicking and scrolling. Enlightenment ideals or critical thinking do not drive engagement; outrage and affirmation do. Thus, even if unintentionally, these companies have as much of a stake in a distracted, intellectually passive population as any medieval monarch did in an illiterate one. The tech giants won’t come out and say they prefer an ignorant user base – in fact, their marketing often proclaims the opposite, using buzzwords about “connecting knowledge” and “empowering learning.” But the reality is that an algorithm finds it easier to hold your attention with sensational misinformation or tribal rage-bait than with a nuanced documentary or a long-read investigative piece. So instead of a censored populace (the old model of keeping people in the dark), we have an overloaded populace – drowning in so much noise and ephemeral content that meaningful signal is hard to discern.

Plato once feared that the written word would “flood” the mind with too much to remember; how would he regard an era where every individual carries a device that can access virtually the entirety of human gossip and trivia in seconds? We have built a machine that ensures no one has to be bored – and yet we’ve lost something essential in never being still. The outcome of all this is that enlightenment-era values – reason, critical debate, scientific scepticism, secular and humane ethics – are dimming. In their stead, a kind of neo-medieval mentality is creeping back in.

Superstitions and conspiracy theories that should have died out under the harsh light of universal literacy are crawling out of the shadows, invigorated by the ease with which even the most absurd notions can find an online echo chamber. Measles, which science had nearly eradicated through vaccines, is resurging in some regions because influential voices on social media sow doubt about basic immunology – a scene not unlike old folktales of ignorant villagers refusing medicine for fear of witches’ potions.

On university campuses and intellectual arenas, we see a hardening of tribal identities and ideologies, often at the expense of open inquiry and tolerance – a regression to the kind of factional, sectarian thinking that the broad perspective of literature and history education was meant to transcend. And as wealth and information control become ever more concentrated at the top – in a new techno-oligarchy – the average citizen finds themselves increasingly baffled about how the world really works, and thus powerless to effect change. In such a milieu, many simply give up and retreat into personal distractions or rage at caricatured enemies, while a sophisticated elite quietly manage the levers of power. It is a tableau that would look ominously familiar to someone from the 12th or 13th century.

Where do we go from here? For now, it appears we are hurtling toward a new cultural inflection point – or perhaps a systemic bifurcation. Down one path lies a kind of digital feudalism: a post-literate society stratified by access to real knowledge, where an information-savvy upper class rules over a majority mired in misnavigated data and manipulated emotion. Down the other path – one can still hope – lies a renaissance of awareness, wherein we learn to integrate our miraculous new technologies into a framework that still values and promotes deep, critical thought.

The difference between these futures will depend largely on whether we can adapt our behaviours and institutions fast enough. This is not the first time humanity has faced such a pivot. We might recall that after the fall of Rome’s literacy, it took centuries and monumental effort to reassemble the pieces of knowledge for the Renaissance. Perhaps we have advantages now: we know what is happening in real time, and we have tools (including AI and digital media themselves) that could be repurposed to revive a culture of focused learning instead of undermining it.

Educational systems might evolve – indeed, must evolve – to treat media literacy and concentration as basic skills as important as traditional reading and writing. We could envision technologies designed not to distract, but to cultivate attention – imagine reading apps that reward endurance and insight, or social networks that encourage meaningful discussion over clout-chasing. Society has at least begun to stir with these recognitions: “digital detox” movements, the resurgence of printed books among some younger readers seeking an escape from screens, even legislative discussions about regulating the most dopamine-triggering features of apps. These are nascent signs, but they indicate a pushback, however modest, against the total absorption of life by the screen.

Please do not misunderstand me. Confronting the post-literate future is not about demonising technology or pining for a romanticised past. On the contrary, it’s about remembering what made us modern in the first place: the ability to think beyond the immediate, to gain wisdom from those who came before, and to reason together about what might lie ahead.

The tools have changed, but those needs have not. If we allow reading – that most humble, profound act of syncing one mind with another through time and space – to wither, we risk more than nostalgia for the tactile feel of paper and print. We risk undoing the very gains that print culture brought: the widening of our intellectual horizons, the sharpening of our critical faculties, the capacity to govern ourselves with reason and empathy rather than fear and myth.

The post-literate society looms as a warning. By no means inevitable. It’s like standing at a crossroads where one road leads to an accelerating descent into a new “dark age” of sorts – a world of high-tech connectivity but low collective wisdom – and the other toward a conscious evolution of how we use our minds and our machines. We have, in a sense, been here before. Let’s hope we have the clarity to chart the right course, to ensure that the light garnered over centuries of reading is not extinguished but rekindled in forms appropriate for the future.