Everywhere I look in Western societies today, glaring cracks have appeared in their civic foundations. Political polarisation has hardened into bitter rancour; social bonds are fraying amid deepening divisions and mistrust. We are witnessing surges of antisemitism and Islamophobia, seemingly random acts of violence, and a compliant media bending to corporate power rather than challenging it. Meanwhile, an unchecked military–industrial complex runs rampant, emulated by an equally unbridled Big Pharma complex hijacking medical agendas. An effective monopoly of influence – captured by well-funded lobbies, billionaire donors, and corporate interests – has thoroughly warped the ideals and practice of democracy.

In truth, our so-called leadership – a misnomer these days – seems less interested in serving the people than in preserving a status quo that profits the few: themselves, their cronies, and big business. Small wonder that public trust in officialdom is evaporating.

Even on the international stage, the rule of law has been gravely undermined, and nowhere is this more evident than in the waning authority of the United Nations, the World Health Organisation, and the International Court of Justice. This principal judicial organ of the UN was conceived as a pillar of global justice – an impartial forum where nations could resolve disputes under law rather than force. Yet today, the world’s heaviest hitters routinely sidestep or ignore it, leaving the ICJ increasingly toothless. Powerful states cherry-pick when they recognise its jurisdiction, and when verdicts prove inconvenient (as with the US rejection of the ICJ’s ruling in the Nicaragua case of the 1980s), they simply flout them. Accordingly, the high ideals enshrined in The Hague’s Peace Palace too often ring hollow. The Court may issue learned judgments, but without the political will of great powers to heed them, those judgements gather dust.

This eclipse of the ICJ’s authority is part and parcel of the broader erosion of international norms. Just as corporate lobbies warp domestic democracy, so too do superpower politics warp global justice. We see some nations exempting themselves from accountability – signing treaties “à la carte,” vetoing enforcement measures, or withdrawing from the Court’s compulsory jurisdiction whenever it suits their interests. Such manoeuvres reduce the ICJ to a court of the willing; its reach seldom extends beyond those states who consent to be bound, which notably excludes most of the mightiest players. It is a tragic irony: those most capable of breaching international law often place themselves beyond the law’s reach, rendering the scales of justice lopsided before cases are even heard.

The consequences of a marginalised ICJ are profound. When the world’s highest tribunal can be shrugged off, it sends a dangerous message – that might ultimately makes right, and that the commitment to international law is optional. This fuels a cynical cycle: smaller states lose faith in multilateral justice if they see double standards, while powerful states double down on realpolitik, calculating that tribunals carry no real bite. Over time, the very concept of a rules-based international order deteriorates. Borders are redrawn by force (think of recent conflicts where international verdicts were brushed aside), and global agreements – from maritime boundaries to nuclear treaties – become precarious if there’s no credible arbiter to enforce them.

Yet, just like the hairline fractures in our domestic systems, these cracks in global justice are not beyond repair. The ICJ’s declining influence is not due to a failure of wisdom or integrity on the part of its judges – their jurisprudence remains sound, often morally courageous – but rather a failure of collective political courage. Cowardice! The Western empire in particular, which once championed the idea of an international court, must confront its own hypocrisy in undermining it. There is a case to be made that revitalising the ICJ – investing it with broader jurisdiction, streamlining its procedures, and crucially, respecting its decisions even when inconvenient – could help shore up the entire edifice of international peace. After all, a world that drifts back to “might makes right” is a world courting disaster.

In essence, the plight of the ICJ symbolises the crossroads at which we stand. Will we reaffirm that laws – not sheer power – should govern relations among states? Or will we slide further into a geopolitical free-for-all, where only the rhetoric of justice remains while its substance disappears? The answer will determine whether global society can move beyond the failing project of Western hegemony to a genuinely fair international order. As cracks split the old façade, we have a chance – and a duty – to fortify the pillars of justice anew. Only by doing so can we ensure that the next chapter of the human project is not defined by the law of the jungle, but by the rule of law that even the mighty must obey.

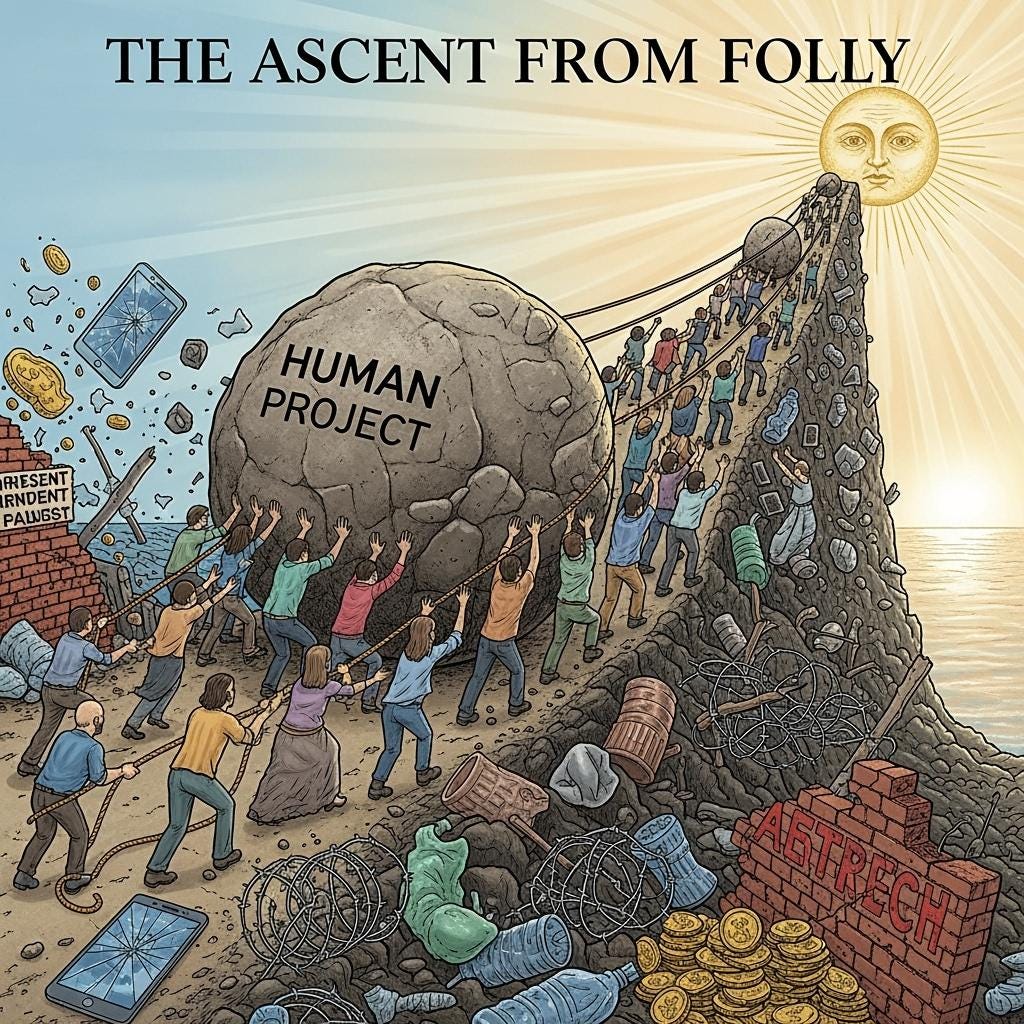

Unfortunately we cannot remain too hopeful. The very sense of belonging to a shared project is unraveling before our eyes. It is as if the grand social experiment of the modern West, borne on the back of the 18th century Enlightnment, and heralded as the pinnacle of human progress, has begun to implode under the weight of its internal contradictions. In effect we’re allowing the human condition to deteriorate to such an extent that we now stand on the edge of a cultural abyss – partial extinction has even become a real possibility.

Yet solutions remain within reach. Escape from this trap will only become possible if we willingly transcend our ingrained obstinacy, hubris and greed. After all, far greater benefit clearly flows from cooperation, trust, generosity and love than from those vices. If our civilisation cannot rediscover these core values soon, then yes – we will likely need a revolution. Not a coup or a bloodbath, but a revolution of the spirit and the social order. And of necessity, it must be a grassroots revolution, rising up from the countless small acts and communities of people, because the incumbent powers have shown no interest in truly changing course.

In times like these, I take heart from examples that prove another way is possible. One of the most inspiring is the Sarvodaya Shramadana Movement in Sri Lanka – a 65-year-old experiment in people-powered change that effectively built a parallel society from the bottom up. In the 1950s, amid poverty and political turmoil, Sarvodaya’s founder A.T. Ariyaratne didn’t wait for government rescue or top-down reform. He went to remote villages with a simple proposition: come together – across political, ethnic and religious divides – to solve your own problems. Villagers who had been divided by old feuds and fears found common ground through shramadana, the “gift of labour”, pooling their sweat to dig wells, build schools, tend to the sick, and plant trees. In doing so, they were practising self-reliance rooted in compassion and shared humanity.

Over the decades this movement grew village by village. By the 2000s, Sarvodaya had an active presence in thousands of villages, touching the lives of millions. It became the largest indigenous development organisation in the country – not by wielding power from above, but by empowering communities to uplift themselves. What transpired in those villages is remarkable. Tamil, Sinhalese, Buddhist, Hindu, Christian, Muslim – it didn’t matter. Working side by side on practical projects, people began to see each other as human beings rather than rivals. They discovered that in building a road together, the road was also building them – forging bonds of trust as strong as the asphalt under their feet.

Sarvodaya provided clean water, schools, and livelihoods, but perhaps even more importantly it rekindled a sense of solidarity long eroded by cynicism and conflict. Tellingly, when a massive tsunami devastated coastal Sri Lanka in 2004, Sarvodaya’s network mobilised within hours – village volunteers from across the nation rushed to deliver relief, even reaching areas that official authorities did not get to until much later. It was people power in action: a grassroots capacity to respond and rebuild, born from decades of practising mutual aid. For me, Sarvodaya is not just a local success story; it is living proof of a global truth: that ordinary people, united in common purpose, can achieve what no isolated individual or distant government could.

And Sarvodaya is far from alone. It stands in a long lineage of communities that have discovered the path to renewal runs through cooperation, generosity, and love. This is what I call the Ecority Blueprint – the recurring pattern throughout history where people facing crisis turn to each other and find strength through solidarity, love and light. Consider the Mondragón cooperatives in the Basque region of Spain: in the 1950s, under the shadow of dictatorship and poverty, a Catholic priest helped local workers form a cooperative factory. They built it on principles of democracy and shared prosperity. Over time, that one workshop grew into a federation of cooperatives – producing everything from machinery to retail goods – which today employs tens of thousands and remains worker-owned and worker-run. Mondragón’s success, enduring to this day, shatters the myth that you need capitalist bosses at the helm; it shows that workers, by trusting each other and pooling knowledge, can create thriving enterprises and distribute the fruits fairly.

Or look at the highlands of southern Mexico: after generations of exploitation, indigenous Maya communities in Chiapas said “¡Basta!” and, in the 1990s, formed autonomous municipalities – the Zapatista communities – where they govern themselves, run their own schools and clinics, and farm their land communally. Despite facing military harassment and economic blockade, those communities have persisted for nearly thirty years, a testament to the power of dignity and grassroots democracy. One could point also to the rise of ecovillages and Transition Towns across the world, from Findhorn in Scotland to Auroville in India, and hundreds of places in between. In these, small groups experiment with low-impact living, renewable energy, local food production, and participatory governance. They are, in effect, micro-societies modeling the changes needed for sustainability. Though tiny in scale, they exert an outsised influence by innovating solutions that larger societies can later adopt. These examples – Mondragón, Zapatistas, ecovillages, and many more – form a tapestry of grassroots innovation. Each is a thread of hope, and together they are weaving the outline of a new civilisation within the shell of the old. They prove that another way is not only possible – it’s already being practiced.

Why do these “alternative” communities matter so much? Because they remind us of a fundamental truth we have forgotten in the West’s contemporary experiment: we humans are at our best when we work together for the good of all. The notion that life is a ruthless competition of each against each is a relatively new and cynical story – one that gained prominence alongside industrial capitalism and has been pushed by those who profit from division and despair. But our deeper heritage, from time immemorial, is one of collaboration. Anthropologists tell us that for tens of millennia, our ancestors survived and thrived not through cut-throat greed but through intense cooperation within tribes and networks of exchange among tribes. Sharing food, raising each other’s children, caring for the sick – these are ancient human norms.

The world’s great spiritual traditions all echo this truth. The Jewish prophets and Jesus placed love and compassion above legalism and power, urging us to care for the stranger and the downtrodden. The Buddha taught that the origin of suffering is selfish craving, and that by relinquishing attachment and cultivating compassion we can find liberation – a lesson not just for individuals but for whole societies caught in materialistic obsession. The Stoic philosophers in the Roman Empire insisted on virtue, simplicity and resilience, famously reminding themselves that “that which is not good for the hive is not good for the bee”– in modern terms, if our economy or politics harms the community (the hive) or the planet we all share, it is ultimately harming each of us as individuals (the bees). The Taoists in ancient China counselled living in harmony with the Tao (the natural way), rather than forcing an unnatural order; they warned that excessive control and aggression would backfire, and praised those leaders who govern the least and live humbly. Islam, too, joins this chorus: the Qur’an repeatedly insists on justice, mercy, and the wellbeing of the community as bedrock principles. “O you who believe! Stand out firmly for justice, even against yourselves,” it enjoins. The Prophet Muhammad said, “None of you truly believes until he wants for his brother what he wants for himself,” teaching a golden rule of empathy and mutual care.

Across continents and epochs, the message is strikingly consistent: if a society elevates greed, falsehood and domination, it will fall; if instead it upholds empathy, truth and shared humanity, it will rise. In my own work and life, I have found that whenever a community returns to these basic values, a kind of social healing begins almost immediately. Trust is restored. People feel safe to reach out to one another again. New ideas flourish because the fear that kept us isolated diminishes. The “ecority blueprint” for renewal is not outdated– it is encoded in our very nature, waiting to be activated by necessity or vision.

Today’s Western crisis, then, can be seen as a direct result of straying from this blueprint. We built towering systems – vast economies, powerful states, sophisticated technologies – but we emptied them of the human values that give systems life and legitimacy. We have gadgets and wealth undreamt of by our ancestors, and yet people are lonelier, more anxious, more distrustful than ever. We have global institutions and expert managers, yet our societies feel rudderless and cynical. Why? Because no amount of top-down control or material abundance can substitute for a sense of shared purpose and genuine community.

A century ago, the sociologist Émile Durkheim warned of anomie – a condition of rootlessness and normlessness that arises when social bonds and shared values break down. I would argue that much of the Western world now lives in a state of anomie. The old norms (patriotic duty, religious piety, belief in unending progress) have largely faded or turned hollow; the new norms (celebrity-worship, consumerism, hyper-individualism) provide no real comfort to the soul. In this void, people grasp for scapegoats or sedatives. Hence the polarisation – each faction clinging to some brittle identity because a larger sense of belonging eludes them. Hence also the epidemic of addictions and the banal escapism of consumer culture.

But if the disease is disconnection and purposelessness, the cure is reconnection and meaning. And those are precisely the fruits that the grassroots movements I’ve described seek to cultivate. They reconnect us – to each other, to our tribe and locality, to our own potential for agency. They restore meaning – by inviting us to be part of something larger than ourselves, something actually constructive. I have seen this firsthand countless times: when people join together in a shared endeavour, whether it’s starting a community garden or organising a neighbourhood watch or launching a cooperative business, they are not just solving a practical problem; they are healing an invisible wound. The wound of isolation, of feeling that one’s life doesn’t matter to others. Suddenly, through collective action, individuals feel seen and valued, and a virtuous cycle begins. Trust grows. And trust, as Confucius wisely noted, is the one thing no society can do without – “If the people have no trust, the state cannot stand”.

If there’s one glimmer of hope in our present darkness, it is this: a grassroots renaissance is already taking shape, under the radar and largely unnoticed by those in power. While governments stumble from crisis to crisis, ordinary people are building new forms of community and economy in myriad ways. If you visit some of these emergent initiatives, as I often do, you quickly realise that they are drafting a blueprint for the future. I think of the community land trusts taking housing off the speculative market so that families can actually afford homes. I think of the cooperative banks and local credit unions proving more stable than the big banks because they invest in real communities and not in reckless gambles. I think of peer-to-peer networks that allow creators and users to share music, software, knowledge, bypassing corporate gatekeepers. I think of citizen-led assemblies in places like Ireland and France, where randomly selected citizens deliberate on thorny issues (abortion, climate policy) and produce solutions far more enlightened than what career politicians have managed in years – showing that ordinary people, given information and a forum, can govern themselves with wisdom. Each of these develops independently, but one can already imagine them linking together in a coherent world-system. In fact, this is how profound change always happens: disparate innovations start to converge. The once-isolated experiments find each other, learn from each other, and gradually form a new normal.

Of course, none of this is to suggest that transition is ever easy or automatic. The gravitational forces of the status quo are daunting. They will not simply roll over. Every grassroots movement that gained momentum has faced pushback – sometimes fierce – from those who benefit from the existing order. The labour unions of the 19th century fought bitter battles (sometimes literally) against factory owners and hired thugs to win basic rights. The civil rights activists in America braved jail cells and attack dogs. The suffragettes were mocked, beaten, force-fed in prison. Even a non-violent revolution like Gandhi’s satyagraha in India met brutal repression before it eventally prevailed.

We must be prepared for similar resistance. And yet, history also teaches that once the collective will of the people reaches a certain critical mass, no power can ultimately withstand it. Regimes that seemed invincible suddenly crack: the Berlin Wall falls; apartheid crumbles; dictators are toppled by crowds in the streets; empires dissolve. Why? Because power, in the end, rests on consent – even if that consent is manufactured or coerced. When the spell breaks, when enough people withdraw their consent and assert their own agency, the mighty are left with nothing but their shadow and an empty title.

We’re nearing such a breaking point. You can sense it in the global waves of protest (for racial justice, for climate action, for economic fairness, for an end to the Palestinian genocide). You can find it in surveys showing plummeting faith in traditional political parties and mainstream media. People are not apathetic; they are yearning for change but often don’t see a clear path. Our job – those of us who see the Ecority Blueprint and the potential it holds – is to illuminate that path and walk it ourselves. We have to demonstrate, through action, that there is an alternative to cynicism and submission.

One key insight I’ve gained over the years is that fighting the existing system head-on, on its own terms, often only feeds it. Direct confrontation has its place, to be sure – speaking truth to power, protesting injustice – but if we pour all our energy into negating the old, we may neglect to build the new. This is why I often invoke the advice attributed to Buckminster Fuller: “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”. The beauty of the grassroots movements described earlier is that they are doing exactly that – building new models, here and now. Instead of waiting for permission, they are creating parallel institutions founded on fundamentally different values.

Over time, if nurtured, these alternatives can grow to a point where the old system simply becomes irrelevant for more and more people. They offer a peaceful, evolutionary path to revolution: eroding the power of the status quo not by frontal assault, but by siphoning away its legitimacy and its participants. For example, if enough towns generate their own green energy, gigantic fossil-fuel utilities lose their monopoly and political clout. If enough young people get educated via open online courses or community learning co-operatives, universities and lenders are forced to reinvent themselves or lose relevance. If more citizens start deliberating and shaping policy at the local level, the grip of polarising partisan theatrics in national politics weakens. In short, we can begin to live the future now. This doesn’t mean the transition will be seamless – there will always be friction, moments of uncertainty as the two paradigms collide – but it shifts the locus of initiative to us, the people, rather than leaving it in the hands of those defending the past.

I want to emphasise that this needed revolution is not merely about outer structures, but about inner transformation as well. It asks us to rethink our own values, needs and habits. It’s too easy to point fingers at corrupt politicians and greedy CEOs – especially when they’re also sociopaths. And many of them do deserve censure. But a revolution of love and cooperation also requires each of us to examine ourselves. How much have we internalised the ethos of the prevailing system we now oppose? Do we catch ourselves indulging in prejudice, or hoarding more than we need, or chasing status symbols, or turning a blind eye to suffering?

Breaking free from a toxic status quo is not a spectator sport; it’s a deeply personal journey too. In the 1960s, Jiddu Krishnamurti shrewdly observed, “It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.” He meant that if you feel alienated by today’s world, that may be a sign of sanity, not sickness. To heal society, we may first need to unlearn the social conditioning within ourselves that treated this insane folly as normal. Fortunately, working on inner growth and working on outer change can go hand in hand. As we engage in community projects, we often find our own fears and biases softening. Service can be a form of spiritual practice. Conversely, cultivating empathy and mindfulness in our personal lives makes us more effective collaborators and activists. The Ecority Blueprint has always recognised this interplay: the outer revolution and the inner revolution are part of the same process of human awakening.

So, what does all this amount to? It amounts to a call to action – arguably the most urgent and virtuous call of our age. We – each and every one of us alive today – have the chance to be midwives to a new civilisation. The Western empire as we know it may be faltering, but something new and beautiful can be born from its lessons and its failures. We possess more knowledge, more tools, and more interconnection than any generation before us. Others, not seduced by Western principles, have been working on their own regenerative purpose. Imagine if we can come together, putting them at the service of that ancient set of values we never truly lost. In practice, this means millions of conversations, projects, and experiments blooming across the globe – a great collaborative venture to rebuild the human project on a sounder and more humane footing. Some might roll their eyes and say people are too selfish or that change is too hard. I say: look again at Sarvodaya, at Mondragón, at countless other stories. People are capable of remarkable selflessness and ingenuity – when given the opportunity and inspiration. Human nature contains greed and folly, yes, but also immense reserves of empathy, courage and creativity.

The narratives we choose to elevate will shape which side of our nature dominates. If we keep feeding a narrative of submission and despair – “nothing can be done, the world is going to hell” – we shouldn’t be surprised if that becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. But if we start telling a new story – of common purpose, of turning breakdown into breakthroughs – we give ourselves permission to act from our highest nature. And then watch what happens. I have often been happily surprised by how quickly situations can improve once people wholeheartedly decide to make it so. As the anthropologist Margaret Mead famously noted, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” The small groups are already gathering. The committed citizens are finding each other.

I began by describing the darkness around us; let me end by affirming the light that is emerging. In the face of growing polarisation, we see courageous individuals building bridges across divides – dialoguing in good faith where politicians dare not. In the face of social fragmentation, we see community organisers turning disused spaces into commons where neighbours meet and cooperate. In the face of violence, we see unarmed movements for justice that appeal to conscience and often win over the undecided. In the face of media manipulation, we see independent journalists and open-source investigators shining a light on truth. In the face of rampant industrial excess, we see permaculturists and “rewilders” healing land and water with astonishing speed once the intervention of exploitation stops. All these are rays of light, converging. Our role is not to simply admire them, but to join them – to connect them – to amplify them. The revolution that will heal our world will not come from one messiah or one ideology, and most certainly not from one nation. It will come from all of us, finding common cause at the grassroots and rising as one to say: we can do better. We can live by the eternal values of honesty, kindness and fairness – and use them to design innovative systems fit for the 21st century. We can honour our interdependence with each other and the planet – and from that place of humility, discover entirely new possibilities for human flourishing. We can become the bridge between tradition and transformation.

I waver between optimism and pessimism. But I do not lose hope. I return often to that ecority blueprint, and I see there the seeds of our future. If we water those seeds – through our actions, through our choices every day – they will grow into something resilient and true. The bonds of trust and belonging can be rewoven, stronger than before, if we attend to them with care.

The Western world may well have to pass through a reckoning, but on the other side of that is the potential for a great renewal. In a hundred years, people could look back and say, “That dark time in the early 21st century? It was the chrysalis from which a new culture emerged.” A culture not of empire or exploitation, but of community and balance. This is the vision that guides me as I work on initiatives like The Ecority Trust, striving to prototype a more equitable, sustainable economy. And it’s the vision I see reflected in unheralded acts of courage and kindness around the world.

We have not yet lost our way completely – not as long as groups of neighbours still help each other in a crisis, not as long as idealistic young people still volunteer to teach or plant trees or hack solutions for the public good, not as long as elders still pass on wisdom about how to live in harmony. The revolution has already begun in countless hearts and communities. Now it must spread and link up, until it becomes an undeniable force.

The choice before us cannot be postponed indefinitely. Either we continue on our current path – in which case disintegration and despair will be our lot – or we consciously break with the status quo and chart a new course. No one else is coming to do it for us; we are the leaders we have been waiting for. I believe that if we answer this call, future generations will thank us with full hearts. And if we fail, they will rightly ask why we did not act when we still had the chance. So let’s act – with wisdom, with urgency, with with love and with light. Let us, in our own lives and communities, embody the change that our world so desperately needs. In the words of Mahatma Gandhi, let us “be the change we wish to see in the world.” And let us remember that the most powerful tools we have are not missiles or money, but the age-old virtues of cooperation, generosity and love. Guided by those, we can rebuild the world. We have all the tools we need – we have each other.

The Ascent from Folly

Working to Get the Human Project Back on Track

Oct 09, 2025